Between source and sea: The role of wastewater treatment in reducing marine microplastics

Shirra Freeman1, 2, Andy M. Booth3*, Isam Sabbah4,5, Rachel Tiller3, Jan Dierking6, Katja Klun7, Ana Rotter7, Eric Ben David4, Jamileh Javidpour8, Dror L. Angel9, 1

- Recanati Institute of Marine Studies, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

- National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health, Vancouver, Canada

- SINTEF Ocean, Trondheim, Norway.

- Prof. Ephraim Katzir Department of Biotechnology Engineering, Braude College, Karmiel, Israel

- The Institute of Applied Research, The Galilee Society, Shefa-Amr, Israel

- GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Marine Ecology, Germany

- National Institute of Biology, Marine Biology Station, Piran, Slovenia

- Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark

- Department of Maritime Civilizations, Leon Charney School of Marine Science, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

*Corresponding author: andy.booth@sintef.no, +47 93089510

Systematic literature search protocol

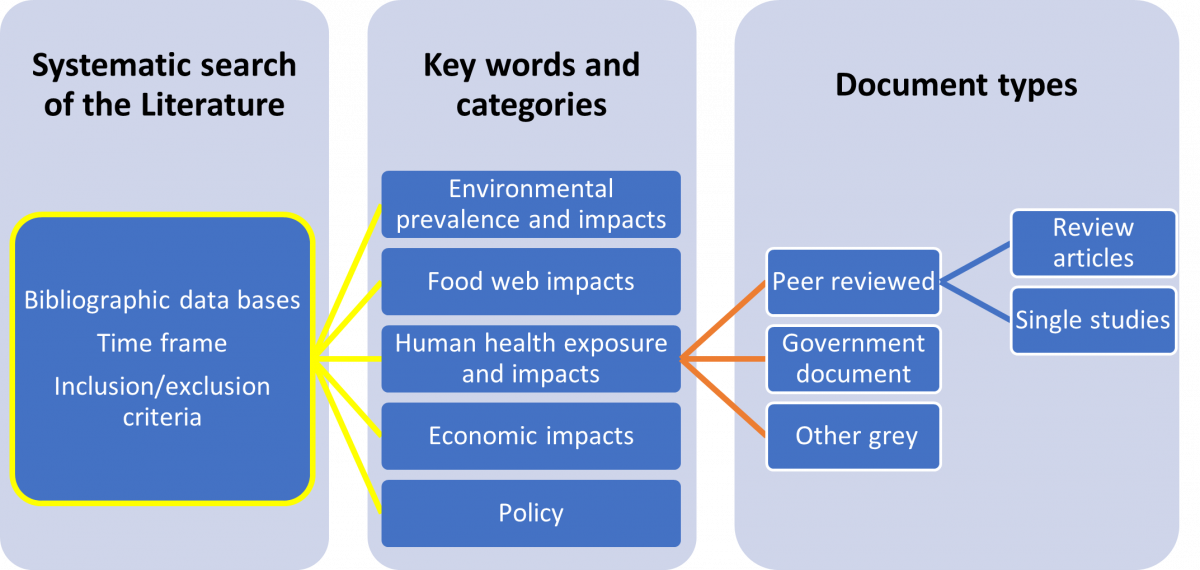

Two systematic searches of the literature were conducted, the first in February 2018 and the second in July 2019. The objective of the first search was to determine areas in which research had been focused in order to scope links between marine MP and human health, while the second search served to update the first. The overall search strategy is summarized in Figure 1.

1. Systematic search and selection of literature method.

Articles were obtained from the University of British Columbia’s EbscoHost (which included access to Medline, CINAHL, and Biomedical Reference Collection), Ovid (Embase), Web of Science, EconLit, Google Scholar and Google. The initial set of search terms were unrestricted by year and included variants and Boolean combinations of the following keywords: marine, microplastic, litter, debris, pollution, particle, environment, food chain, food web, waste water, organism, human health, economic. Separate searches were conducted for governments and agencies including FAO, UNEP, OECD, WHO, NGOs and professional organizations (See Table 1 below).

Table 1. Specialist organizations consulted.

|

ORGANISATION |

WEBSITE |

|

European Environmental Agency |

|

|

European Commission (Science Hub) |

|

|

European Maritime Affairs & Fisheries |

https://ec.europa.e/info/departments/maritime-affairs-and-fisheries_en |

|

European Marine Board |

|

|

European Public Health Association |

|

|

Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) |

|

|

Eurostat |

|

|

Healthy oceans, healthy people |

|

|

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) |

|

|

Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection |

|

|

National Institute of Environmental Health Science |

|

|

National Oceanographic Service (NOAA) |

|

|

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) |

|

|

The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity |

|

|

United Nations Environment Programme |

|

|

World Health Organisation |

|

|

European Water Association |

|

|

Eureau |

|

|

Canadian Wastewater Association |

|

|

American Water Works Association |

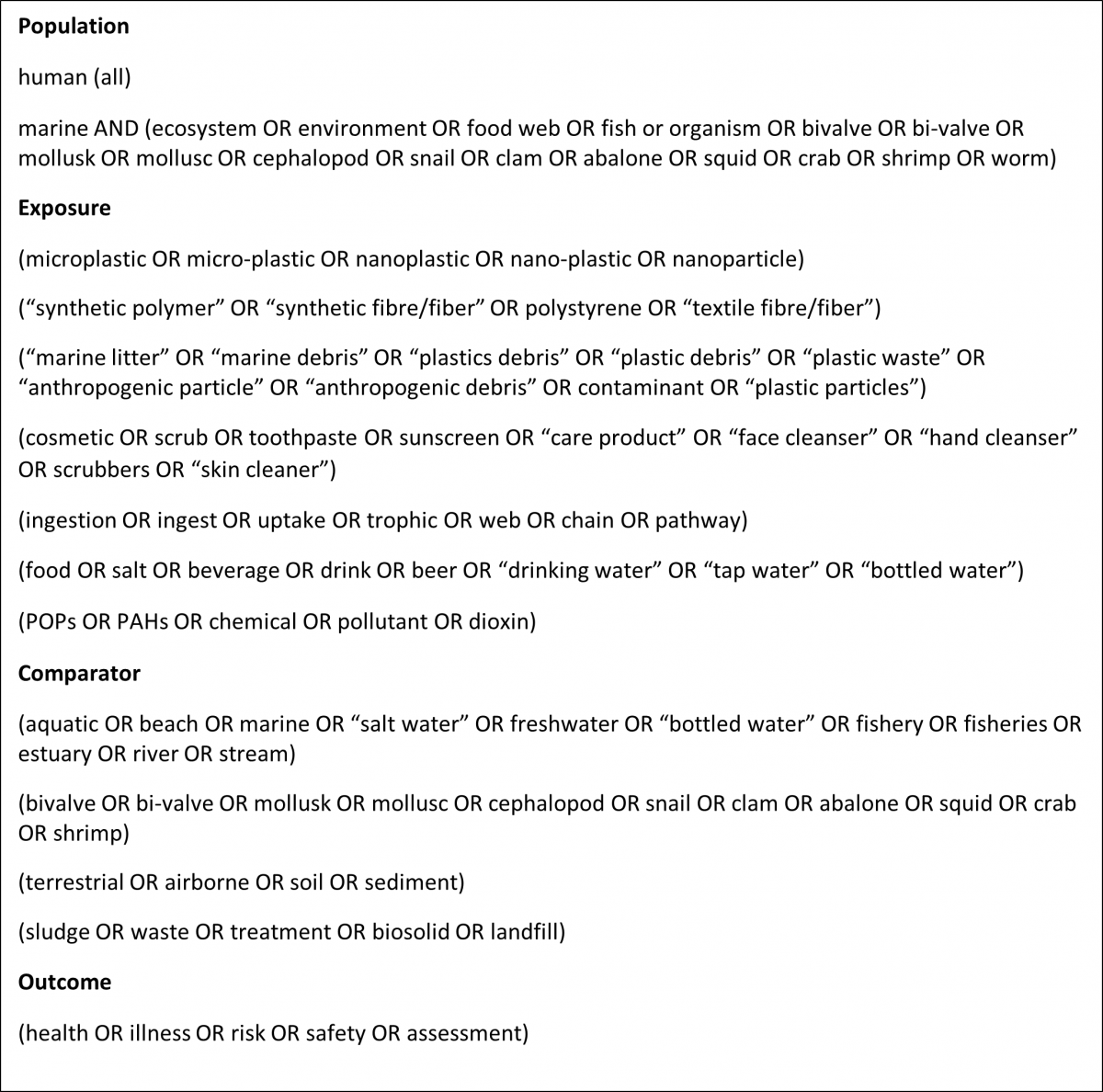

This first set of searches was conducted by three researchers and returned ~2,500 hits. A screening of titles and modification of keywords was employed to exclude studies focused exclusively on polymer classification, materials engineering and manufacturing, analytical chemistry and screening or detection methods, as well as studies whose main focus was not debris in the form of marine MP. The selected keywords were structured on three sets of PECO (Problem/Population, Exposure/ Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) criteria summarized in Table 2 (Health Evidence 2018, Collaboration for Environmental Evidence 2018).[1] Box 1 provides an overview of the PECO keyword structure:

Table 2. Key PECO elements guiding the literature scan.

|

PROBLEM/ POPULATION |

EXPOSURE/ INTERVENTION |

COMPARATOR |

OUTCOME |

|

MP presence and dynamics in marine ecosystems and food webs |

Exposure of marine waters, sediments, coasts and organisms to MP |

No exposure or exposure gradient |

Changes to environmental quality indicators or indicators of organism health. |

|

MP presence and dynamics in environmental media that may lead to marine pollution |

Interventions to remove MP |

No intervention |

Benefits and/or costs of implementing intervention; effectiveness of intervention measured by decrease in MP reaching marine environments. |

|

Adults, children and communities |

Exposure to MP |

No exposure to MP or alternate points along exposure gradient |

Adverse or beneficial impacts on health and/or wellbeing |

1. PECO keyword structure.

The number of hits following this process was approximately 1,000. Further hand screening of titles and abstracts reduced this number to approximately 250 papers that were assigned to the following subject categories:

- MPs in marine environments

- Sources and pathways (e.g., terrestrial, marine, primary, secondary)

- Types (e.g., shapes, sizes, composition, breakdown products)

- Prevalence

- Environmental and food web Dynamics

- Ingestion by marine organisms

- Trophic levels and trophic transfer

- Substrates (e.g., presence in salt, algae, fish, etc.)

- Environmental and food web Impacts

- Hazards and risks (e.g., chemical, physical, pathogens)

- MPs and Human Health

- Sources (e.g., food, water, household and personal care products)

- Exposures (e.g., dermal, inhalation, ingestion, characterization, quantification)

- Toxicology, epidemiology, impact modeling

- Risk characterization

- Waste management

- Solid terrestrial

- Wastewater

- Marine-based activities

- Policy

At this stage, review studies were also distinguished from single studies in each category.

A team of eight researchers reviewed the 250 papers to produce recommendations for including or excluding each from the review process. Reasons for exclusion included (i) lack of content dealing with marine MPs in connection with environmental or human health impacts, (ii) absence of description of methods or inappropriate methods for addressing research question or hypothesis, (iii) results that did not address the hypothesis or research question or were unconnected to methods, (iv) lack of data, (v) conflict of interest, and (vi) publications in languages other than English.

Approximately 100 papers were included in the final list of studies to be reviewed. Of these, approximately 30 were review papers that assessed one or more research questions based on existing literature. The remainder were studies addressing a particular issue related to marine MPs

Contaminants of emerging concern (CEC)1

The knowledge generation process for contaminants of emerging concern (CEC) is an iterative process composed of multiple stages beginning with a lack of concern due to lack of knowledge (Stage 1) progressing to awareness of a potential threat coupled with an understanding of knowledge gaps that need to be addressed (Stage 2). Once enough knowledge has been accumulated and the threats are better understood, a peak of concern is reached as the focus turns to finding solutions (Stage 3). In Stages 4 and 5, knowledge accumulations and action (e.g., changes in policies and behaviors) is taken. Over time, additional effects related to the CEC may be observed. These may be the result of actions taken in earlier stages or new knowledge related to toxicity, exposure and effects is generated by monitoring, surveillance and research in stages 6 and 7. Stage 8 is characterized by a new knowledge baseline and level of concern that may be stable or may increase if new dimensions of a threat are revealed.

References

1. Halden, R. U., Epistemology of contaminants of emerging concern and literature meta-analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014.

[1] Health Evidence. 2018. Practice Tools-Developing an Efficient Search Strategy Using PICO, available at: https://www.healthevidence.org/practice-tools.aspx#PT2; Collaboration for Environmental Evidence (CEE). 2018. Section 2. Identifying the need for evidence, determining the evidence synthesis type, and establishing a review team. Available at: http://www.environmentalevidence.org/guidelines/section-2.